Ultrasound tracks down misfiring heart sites

New technique improves diagnosis and treatment of abnormal heart rhythms

Abnormal heart rhythms—cardiac arrhythmias—are a major worldwide health problem. Now scientists are using ultrasound for more accurate maps of arrhythmic sites in the heart for improved success of ablation procedures.

Common and often life-threatening, arrythmias can develop when regions of the heart send aberrant electrical signals that disrupt the normal beating of the heart. An effective procedure for fixing this problem involves stealth-like killing of the misfiring regions, known as catheter ablation. The procedure involves feeding into the heart a catheter that uses radiofrequency energy (similar to microwave heat) to destroy the areas causing the irregular heartbeats.

Given that physicians have an effective way to “knockout” these misfiring regions, a key to a successful procedure is accurately identifying the arrhythmic sites. Electrocardiogram (ECG) has been the standard procedure for identifying regions slated for ablation. However, the accuracy of ECG mapping is limited, often resulting in inaccurate or incomplete ablation and the need to repeat the procedure.

Now, NIBIB-funded researchers at Columbia University are using ultrasound to improve the critical need to accurately localize sites causing cardiac arrhythmias. The ultrasound-based technique is called Electromechanical Wave Imaging (EWI).

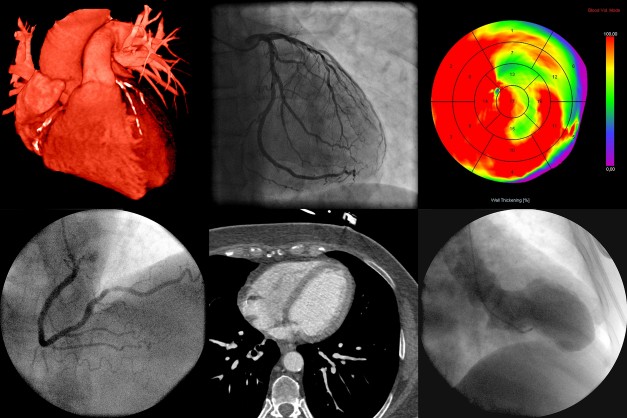

Using portable ultrasound instruments found in most clinical settings, EWI creates 3D cardiac maps that noninvasively pinpoint the electromechanical activity that causes arrhythmias. Another advantage is that the 3D image can be used during the procedure to allow physicians to accurately guide the ablation catheter to the target site.

“This work is an outstanding example of taking a technology that is readily available in hospitals and clinics and adapting it to fill a critical clinical need,” said Randy King, Ph.D., director of the NIBIB program in Diagnostic and Interventional Ultrasound. “Not only does the technique very accurately identify arrhythmic areas in the heart, but it also creates a 3D image of the heart and target sites that guides the ablation procedure in real time.”

The significant improvements offered by the new ultrasound technique were demonstrated at Columbia by the technical team led by Elisa Konofagou, Ph.D., the Robert and Margaret Hariri Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Radiology, through collaborations with the clinical cardiac electrophysiology teams at Columbia University Irving Medical Center led by Elaine Wan, M.D., the Esther Aboodi Assistant Professor of Medicine and Hasan Garan, MD, Dickinson W. Richards, Jr. Professor of Medicine at the Columbia University Medical Center and Director of Cardiac Electrophysiology department.

The team performed both the EWI ultrasound technique and standard 12-lead ECG on 51 patients undergoing catheter ablation. This initial small clinical trial showed that EWI correctly predicted 96% of arrhythmia locations as compared with 71% for the standard 12-lead ECG. The group is now planning a larger long-term clinical trial to evaluate integrating the technique into the clinical setting.

“To work toward integrating the routine use of EWI into the current clinical workflow, future studies will test a number of parameters,” explains Konofagou. “For instance, does the technique reduce the time for the procedure, including reduced time under anesthesia, and does EWI ultimately reduce the cost of ablation procedures? We believe the eventual routine use of the technique could significantly reduce complications and the need for repeat procedures—ultimately providing better outcomes for patients and clinicians.”

The work was supported by grant EB006042 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Scholars Program, the Lewis Katz Prize, the Esther Aboodi Endowed Professorship at Columbia University, the M. Irené Ferrer Scholar Award from the Foundation of Gender-Specific Medicine, and a gift from Howard and Patricia Johnson, and was reported in Science Translational Medicine1.